You have to read this. Dear Omanis, please don't be offended. Thank you Baxter Jackson for brightening up my day.

.http://matadornetwork.com/abroad/15-signs-you-might-have-been-in-oman-too-long/

Random Ramblings about Life in Salalah...

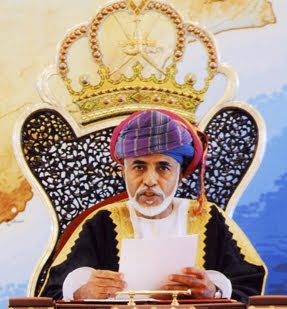

And here she is .. in Oman after 30 years,.... looking elegant and preserved as always. What an honor having her here with us. I wonder what she and His Majesty have talked about? I'd LOVE to know what their conversations are like. Does he address her as 'Your Majesty' and vice versa? Have they had an actual conversation? Do you think they've talked about horses? Bagpipes? Perhaps he's asked her what she thinks of Prince William's engagement to Kate Middleton last week? The so called engagement the world has been waiting for (according to Hello magazine). Do they have their meals together? I wonder. . .

And here she is .. in Oman after 30 years,.... looking elegant and preserved as always. What an honor having her here with us. I wonder what she and His Majesty have talked about? I'd LOVE to know what their conversations are like. Does he address her as 'Your Majesty' and vice versa? Have they had an actual conversation? Do you think they've talked about horses? Bagpipes? Perhaps he's asked her what she thinks of Prince William's engagement to Kate Middleton last week? The so called engagement the world has been waiting for (according to Hello magazine). Do they have their meals together? I wonder. . . Eid Mubarak Everyone!

Eid Mubarak Everyone! Many grumbles and moans across the nation this morning! (insert cheerful sing-song voice). Eid holidays for the public sector as follows:

Many grumbles and moans across the nation this morning! (insert cheerful sing-song voice). Eid holidays for the public sector as follows: Yes... believe it or not, Salalah is FINALLY getting its own shopping mall (and don't tell me Isteqrar Hypermarket is a mall). Our new mall (the building is almost finished) is located on the main Rabat highway next to Centrepoint. The mall will include the following blessings:

Yes... believe it or not, Salalah is FINALLY getting its own shopping mall (and don't tell me Isteqrar Hypermarket is a mall). Our new mall (the building is almost finished) is located on the main Rabat highway next to Centrepoint. The mall will include the following blessings: Been too busy to write. More weddings. Monsoon is officially over but the mountains are still green. We had some rain this week, but only in the mountains. Salalah is crammed with police officers and army officers this week as His Majesty is conducting the 2010 Oman Council Meeting in Salalah this morning. Two hours from now.

Been too busy to write. More weddings. Monsoon is officially over but the mountains are still green. We had some rain this week, but only in the mountains. Salalah is crammed with police officers and army officers this week as His Majesty is conducting the 2010 Oman Council Meeting in Salalah this morning. Two hours from now. Only 256,984 tourists visited Salalah this year during the monsoon season (June 21-September 17). Down from 283,754 last year. Probably due to Ramadhan.

Only 256,984 tourists visited Salalah this year during the monsoon season (June 21-September 17). Down from 283,754 last year. Probably due to Ramadhan. Thank you Muscat Mutterings for the wonderful news. I'm glad it wasn't announced at 2 p.m on Wednesday as expected.

Thank you Muscat Mutterings for the wonderful news. I'm glad it wasn't announced at 2 p.m on Wednesday as expected. It's finally happening. Check out this article in today's Oman Observer. Sigh.

It's finally happening. Check out this article in today's Oman Observer. Sigh.

Dear Readers,

Dear Readers, The number of veiled female beggar/wackos around Salalah has been on the rise recently. Many of them have GCC accents but claim to be Palestinian, etc. They accost you in supermarkets and start saying prayers very quickly and asking you for help. You're so annoyed by their fast praying that you immediately shove a couple of rials in their hand to get away from them. They then clutch your hand and thank you profusely. You notice their wrists are heavy with gold and they wear expensive perfume. Their faces are covered so you have no idea what they look like. They creep you out and you try to leave the store immediately.

The number of veiled female beggar/wackos around Salalah has been on the rise recently. Many of them have GCC accents but claim to be Palestinian, etc. They accost you in supermarkets and start saying prayers very quickly and asking you for help. You're so annoyed by their fast praying that you immediately shove a couple of rials in their hand to get away from them. They then clutch your hand and thank you profusely. You notice their wrists are heavy with gold and they wear expensive perfume. Their faces are covered so you have no idea what they look like. They creep you out and you try to leave the store immediately. Hey everyone! As expected, there were no moon sightings yesterday. To those of you who are new to the Islamic world, this is how it works. If Ramadhan is expected on Wednesday or Thursday (depending on the moon and the Islamic calendar), Oman TV will set up studios around the country and all our bearded sheikhs in their white turbans will line up on the fancy gold and red sofas around sunset. Meanwhile, more bearded guys are out in the mountains with telescopes trying to spot the moon. Finally, an hour or so later, His Excellency the Minister of Religious Affairs announces that the moon has not been seen, and therefore, Ramadhan for Oman will not start the next say but the day after. Secretly, everyone knows we won't be fasting till Thursday because frankly speaking, I can't remember the last time we fasted 30 days. Oman's been doing the 29-day trend for years. We always end up fasting a day after Saudi, and we break the fast with Saudi. Is it deliberate? God only knows.

Hey everyone! As expected, there were no moon sightings yesterday. To those of you who are new to the Islamic world, this is how it works. If Ramadhan is expected on Wednesday or Thursday (depending on the moon and the Islamic calendar), Oman TV will set up studios around the country and all our bearded sheikhs in their white turbans will line up on the fancy gold and red sofas around sunset. Meanwhile, more bearded guys are out in the mountains with telescopes trying to spot the moon. Finally, an hour or so later, His Excellency the Minister of Religious Affairs announces that the moon has not been seen, and therefore, Ramadhan for Oman will not start the next say but the day after. Secretly, everyone knows we won't be fasting till Thursday because frankly speaking, I can't remember the last time we fasted 30 days. Oman's been doing the 29-day trend for years. We always end up fasting a day after Saudi, and we break the fast with Saudi. Is it deliberate? God only knows.

I can't believe it's been 40 years since His Majesty overthrew his father (in a bloodless coup) and turned Oman into a modern country. Look how far we've come! I will not join the thousands who will be marching down 23rd of July street today in celebration. I will sit in my favorite spot at the top of the mountains and say a prayer for His Majesty and this wonderful country. Happy Birthday Oman!

I can't believe it's been 40 years since His Majesty overthrew his father (in a bloodless coup) and turned Oman into a modern country. Look how far we've come! I will not join the thousands who will be marching down 23rd of July street today in celebration. I will sit in my favorite spot at the top of the mountains and say a prayer for His Majesty and this wonderful country. Happy Birthday Oman!  After THIRTY YEARS the Queen is finally coming to Oman to celebrate the 40th national day with us. What fun. I wonder whether she will be pulled through HOT Muscat in a carriage with His Majesty :)

After THIRTY YEARS the Queen is finally coming to Oman to celebrate the 40th national day with us. What fun. I wonder whether she will be pulled through HOT Muscat in a carriage with His Majesty :)  Sleep-deprived Nadia on a Wednesday morning isn't something you want to see. I have no idea how I managed to keep track of all four soccer matches yesterday, but I did. And no Rania, I don't hang out at Shisha cafes to watch the games. I gather my female relatives in front of a 52 inch plazma TV in our outdoor majlis with tawa bread, red tea, and Chips Oman.

Sleep-deprived Nadia on a Wednesday morning isn't something you want to see. I have no idea how I managed to keep track of all four soccer matches yesterday, but I did. And no Rania, I don't hang out at Shisha cafes to watch the games. I gather my female relatives in front of a 52 inch plazma TV in our outdoor majlis with tawa bread, red tea, and Chips Oman. (1) Coming to think of it, my daring friends have suggested that a group of us girls walk up to a Shisha cafe on the Haffa Corniche and just pull up chairs and see what happens. Will the world fall apart? Will someone call my father immediately? Will the police come? What WOULD happen? Oh the unwritten rules in this town... I'm sure any Dhofari male reading this now is cringing and probably drafting an email to me advising me to take care of my reputation.

(1) Coming to think of it, my daring friends have suggested that a group of us girls walk up to a Shisha cafe on the Haffa Corniche and just pull up chairs and see what happens. Will the world fall apart? Will someone call my father immediately? Will the police come? What WOULD happen? Oh the unwritten rules in this town... I'm sure any Dhofari male reading this now is cringing and probably drafting an email to me advising me to take care of my reputation. Dear Readers,

Dear Readers, Hey everyone! Another expat married to an Omani on the block! I'd like to welcome new blogger, Sultanate Social, to the Omani blogging scene! I should have welcomed her earlier when I first read her blog, but with the storm chaos and all ........ :)

Hey everyone! Another expat married to an Omani on the block! I'd like to welcome new blogger, Sultanate Social, to the Omani blogging scene! I should have welcomed her earlier when I first read her blog, but with the storm chaos and all ........ :)